I’ve complained before—perhaps over a cup of tea in the staff room, or in the quiet echo chamber of my own thoughts—about the peculiar solitude of teaching CIE Classical Studies 9274. Where was the bustling agora for us? The CIE support hub could be quiet, the Facebook groups a ghost town, and Reddit… well, let’s just say the threads exemplify how few people are crazy enough to take this course. We were a scattered cohort of teachers and learners, navigating this magnificent, dense course largely on our own.

So, I did the only thing a frustrated classicist can do. I’ve created a resource for A-Level Classical Studies 9274, using the same obsessive-compulsive principle as my IGCSE History 0470 one. It’s all here: past papers dissected, topics mapped, and question trends laid bare in an attempt to create the shared foundation I felt was missing.

But let’s get to the fun part. The proof, as they say, is in the pudding.

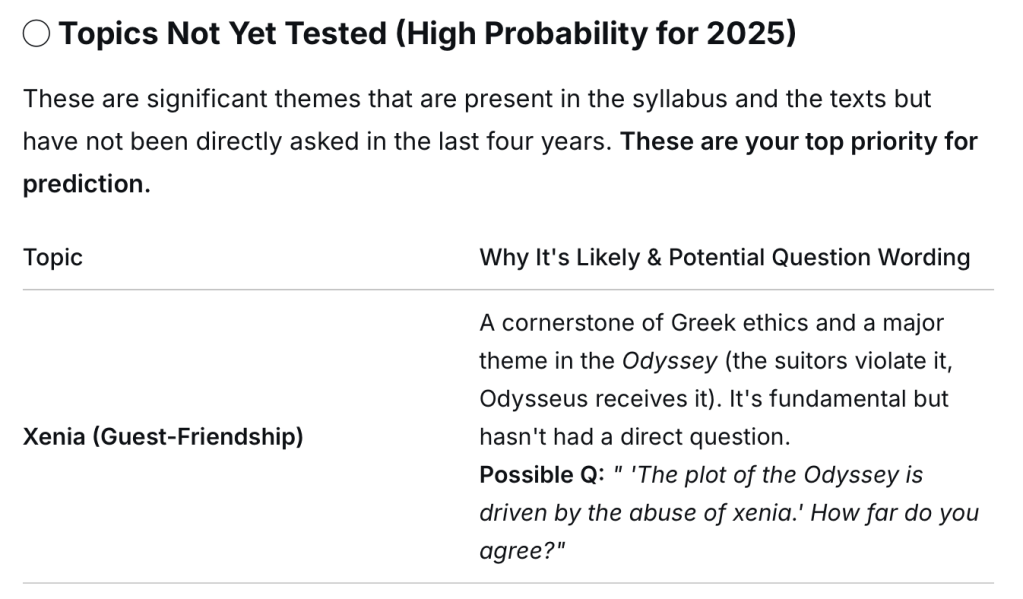

Back in October 2025, as we were deep in the final revision push for the November series, I decided to test a theory. I fed years of meticulously organised data for Paper 4 (Homer’s Epics) into an AI and posed a simple, high-stakes question: Based on the patterns of the last several years, what are the highest probability topics for the upcoming exam?

The AI, coolly analytical, spat out its top candidates. And lo and behold, when my students opened their exam papers, there it was: a question focusing squarely on the theme of Xenia.

Cue my stunned silence, followed by a very undignified moment of triumph at my desk!!! The resource I built to create clarity had just proven its predictive power. A screenshot of that AI conversation is my new favourite piece of pedagogical evidence. Do you need any more convincing of how useful this is?

The point isn’t that we can now gamble on exams. The point is that by systematically understanding the past, we can better prepare for the future. This tool makes that possible.

So, consider this your invitation to the 9274 agora. This resource is here, free for any teacher or learner who needs it. May it save you time, spark your ideas, and maybe—just maybe—give you a glimpse into the mind of the examiner.

If you find it useful, or if you have ideas to make it better, let me know. Let’s stop teaching in isolation and start building this community ourselves. After all, that’s how the classics have survived this long—through shared scholarship, one scroll (or spreadsheet) at a time.