“Heritage sites bear the imprint of the politics of the past at different historical junctures, the meanings of which are now embroiled in the politics of the present.”

– JoAnn McGregor and Lyn Shumaker

Educator and Researcher

“Heritage sites bear the imprint of the politics of the past at different historical junctures, the meanings of which are now embroiled in the politics of the present.”

– JoAnn McGregor and Lyn Shumaker

If you’re up for it, here’s a very long, very sad, very powerful read about public history and living memory in Alabama. It touches on the need to memorialize, to remember, a touching “currency” of memory work, and ends with interesting comment on the spectator’s presence in such lieux de memoires. Have you ever experienced intense emotions in reenactment history? Something about this story collapses temporal and spacial distance. Perhaps it is not unusual for the reader to feel pain and sorrow for a history that still does not feel quite “past” in 2016.

Please give it a read here.

Ironically, this film was created with the community with support and funding from the government. It brings together three spheres of national (government funding), local, (community participation) and public (cinematic mobility and reach). The cinematic becomes a gathering place for renegotiations of authority and agency and transforms into one powerful medium — an impetus for change.

You Are On Indian Land (1969) was filmed in collaboration with a Mohawk activist and filmmaker. This short documentary was part of Challenge For Change, a participatory filmmaking project “braiding” separate threads of power and lack of power into one coherent call to action. The National Film Board project formed The Indian Film Crew in 1968 to encourage, inspire and train First Nations people in filmmaking. Sponsored by private and public stakeholders, participants later went on to work on community development projects.

Affective history has the ability to collapse temporalities. For a film made almost a half-century ago, You Are On Indian Land bears a striking resemblance to present-day politics. The film documents a confrontational “contact zone” where the the Mohawk of the Akwesasene Reserve (then called St. Regis) set up a blockade on a duty road connecting Canada and the United States, where the governments were charging “indians” for crossing on what little was left of their own land. Today, indigenous peoples are part of a new nation, “Blockadia” so termed by journalist Naomi Klein. In places like Standing Rock, Dakota, people are protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline and authorities are using extreme force and incarceration to bully First Nations peoples into submission.

Click on the image to view the film.

There are moments when there can be no objective divorce between the politics of the present and the study of the past. This is one such moment in the political present where the world we live in cannot be removed from the politics of the past, nor the graduate-level public history assignment.

For Canadians who woke up on November 9th, 2016 to a world they no longer comprehend, it is important, now more than ever, to understand the public historian’s role in civil society, consider our responsibilities by virtue of it, and work to assure the Canadian public does not succumb to demagogic narratives of isolationism, fear, and hate.

Our Role

Public history serves the public — a collection of peoples cohabiting spaces with memory and history. Public historians aspire to honest, context and evidence-based truth-telling. This can be achieved by employing diligent historical analysis, championing multiple manifestations of remembering and using evidence-based storytelling to maintain accountability. Done right, public history can engender learning, healing, and individual and collective development. Done wrong, it can contribute to misinformation, suffering, and painful reminders of our shared colonial pasts.

Our Challenges

There are several stories in Canadian public history professionals need to thoughtfully consider before pursuing future projects. Historicization of public history shows the discipline has authored its own uncomfortable chapters in the ongoing colonial narrative. The field needs to adopt a generous and unflinching reflexivity to see it’s own power in shaping public discourses. Andersen puts it eloquently: “spaces of cultural representation— like museums and national historic sites—can be spaces of mutual recognition rather than mere manifestations of colonial power.” Here are some suggestions on how to do that.

What Not To Do

What To Do

“From a piece of the Wright brother’s plane to a child’s sugar egg, today: Things! Important things, little things, personal things, things you can hold and things that can take hold of you. This hour, we investigate the objects around us, their power to move us, and whether it’s better to look back or move on, hold on tight or just let go.”

Gift yourself 1 hour and 1 minute and let hosts Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich from the WNYC podcast Radiolab weave you through 3 stories of what Appadurai calls “the social life of things.” Give it a try! There is no storytelling quite like Radiolab storytelling. If you don’t have the full hour, you can pick and choose which story you want to listen to here. My favourite is: The Seed Jar.

“What is memory? Do we hunt it with a questionnaire or are we supposed to use a butterfly net?”

– James Fentress and Chris Wickham

“Narratives of the traditional simply being replaced by the modern don’t work when we need to take into account not only possible tradition invention but also self-aware nostalgia, retro-fashioning, alternative traditionalities, memory work, and multiple ways of being modern, some of which involve being traditional in new, or even old, ways.” – Sharon Macdonald

Introduction

Ottawa’s Central Experimental Farm was borne in circumstances not dissimilar to the beginnings of the Public History discipline — as a result of Victorian era interest and advancement in the natural sciences. The national historic site has welcomed visitors since its establishment in 1886, and continues to touch, influence and affect people’s memoryscapes. Although the site’s 427 hectares contains all agricultural and research facility, working farm, botanical gardens, arboretum, and interactive learning museum and more, I will herein refer to it as the Farm.

The Farm’s size and scope allow for a multiplicity of directions for historical investigation, but this research will explore how people who visited the Farm as children remember the site as adults, especially at the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum. Building from Andrew Irving’s experimental methodology “staged fieldwork” as outlined by Macdonald, this research will ask persons who encountered the Farm as children to revisit and relive their experiences in conversation with each other in place.

Research Questions

This research will seek to answer these questions: How do people presently remember and engage with their past childhood experiences at the farm? How have their experiences affected their lives? Which temporality is most prominently represented in events of past-presencing – the past or the present, and why? Do children remember authenticity or an “alternative traditionality” at the Farm?

These questions aspire to unlock “possible modes of experience and telling” that exist when persons act in past-presencing in a unique, socially constructed place such as the Farm. The research hopes to highlight the “creative, not fictive” stories people internalize and relive with others as they interact in place.

Theoretical Evidence

Sharon Macdonald’s idea of past-presencing will be influential in this research. Since the farm’s establishment in 1886 as an agricultural innovation facility for the betterment of national health and prosperity, a modern city has erected and enveloped the surrounding land (and today threatens to encroach deeper). The farm exists not only between times, but belongs in a fascinating multitemporality, where the directions of time intermingle in a negotiated reality.

Science, technology, experimentation and agricultural innovation are very much of the present and for the future. However, heritage buildings, an idyllic arboretum, and the paradoxical existence of a farm within the City of Ottawa suggest the Farm may act as a multitemporal heritagescape, as Walsh described socially constructed places with produced social meaning. Is it possible to separate the modern food science museum exhibit from the cows and calves sitting behind a picket-white fence? Memory Park stands at the centre of the Museum, where a barn housing 59 animals was lost in the 1996 fire, memorializing the past and naming the site as a place of sensitivity.

Other buildings destroyed in previous fires were rebuilt in their heritage style. Is memory “stickier” at sites of trauma such as these? How do memories collide at this site? Do these adults see the Farm differently decades later? What memories remain? Perhaps the answer will never be fully complete, because as Opp and Walsh write, “the production of place is always unfinished and uneven.”

Considering Pierre Nora’s idea of lieux de memoire, this research will investigate how modernity and authenticity at the farm may coexist in a place between times. Nora deserves some explaination: a lieux can be understood as the manifestation of the break between what Nora understands “traditional” or “authentic” memory work and history, the hollow product of the memory crisis in modernity. The controversial theory offers historians interesting ways to conceptualize memory negotiations and past-presencing at the Farm. The Farm is a cleaner, decorated, meticulously crafted place of learning and reminiscing, but it is not a real farm. Therefore the reimagined, synthetic farm can be understood as a lieux de memoire or an alternative traditionality, a picture of pastoral rural times in a technologically innovative, urban setting. Today, the Museum exhibits a modified retelling of past agricultural understandings to nostalgic visitors, young and adult, who yearn for more authentic understanding of the world beyond the food on their plates.

Methodology

This research will employ a version on Andrew Irving’s experimental methodology in his research on HIV/AIDS he calls “staged fieldworld,” as outlined in Macdonald’s chapter on differential ethnographic research methods.

Participants will be briefed on general ideas of the research and asked to reflect on memories, past and present, and place. Participants who visited the Farm as children will voice record their oral histories with a partner without the presence of a researcher as they walk through the site. Participants will supplement their storytelling with pictures with a camera whenever they feel a need to document the image. These performative memories will explore the ways persons interact with the past in the present, how they remember events from their past, and understand the layers of memory and emotion in a place between times.

During my preliminary research I was lucky to come across a woman in a bright red wool sweater who has been working at the Museum for 12 years. She was between appointments giving lessons on pumpkin varieties in a small classroom connected to the cow barn. In an impromptu interview, she spoke wondrously of first encountering the big sheep as a small girl. She noted how the barn has remained exactly the same, but the sheep no longer seemed like giants when she returned to work at the site decades later. She offered her own opinions and perspectives on reality at the farm without prompting, signalling this research may be welcome among the community.

Ethical concerns and resulting methodological restrictions often “mute” the voices of children in traditional histories. This research aims to understand childhood stories, memories, and understandings in the structure of adult retellings. Few events can resurface childhood remembering like the company of an old friend or a new but fellow nostalgic companion. This past-presencing through conversations at the Farm could open up a version of the world as people once saw it and proffer some insight into the ways persons push and pull on individual and collective narratives to come to an understood reality.

In avoiding the scripted questionnaire with researcher vis-à-vis subject, this methodology intends to repudiate unidirectional historical narratives and bridge the gap between Nora’s bifurcation of memory and history by urging participants to practice in a form of multitemporal memory work.

Dissemination of Research

The research will be disseminated to the wider community in podcasts, gathered from the audio recordings during research, edited by the researcher. It is understood the finished audio documentaries will not be what Nora considers a “raw” or “authentic” form of memory — but in the murky negotiations of reality and identify in past-presencing, when is it ever?

Works Cited

Pierre Nora’s concept of lieu de memoire, sites of memory urgently negotiated and established in an era of perilous modernization and subsequent cultural amnesia, is obtuse even for a graduate-level public history seminar. The complexity in Nora’s theory lies within his contentious forced binary between ideas of memory and history, where the former exists in a pure, folklore dreamland and the latter in a structured, incompetent reality that destroys the thing it hopes to preserve — memory. Museums, monuments, books, films and sites of significant are lieux de memoires. Oral storytelling and generational transmission of craft skills are milieux de memoires.

I decided to explain this idea to my parents. Using a list of interview questions based off of the Canadians and Their Pasts survey launched in 2006, I asked my mom and dad to think about memory, history, identity, and how they relate to and understand their pasts. I was surprised to discover that despite never encountering Nora, my parents had formed their own distinctions between memory and history and their respective roles within time-space.

Similar to the findings in the survey, my parents, who immigrated from Hong Kong in the 1980s, placed themselves at the centre of their own pasts to reconcile their identities in the present within ethnic/cultural group and country. In the clips of our phone interview below, my parents first discuss their daily encounters with lieux de memoires (photos) and memory-work (gathering with friends to tell stories). Later, they explain their understandings of memory and history…all before I attempted to explain Nora’s concept.

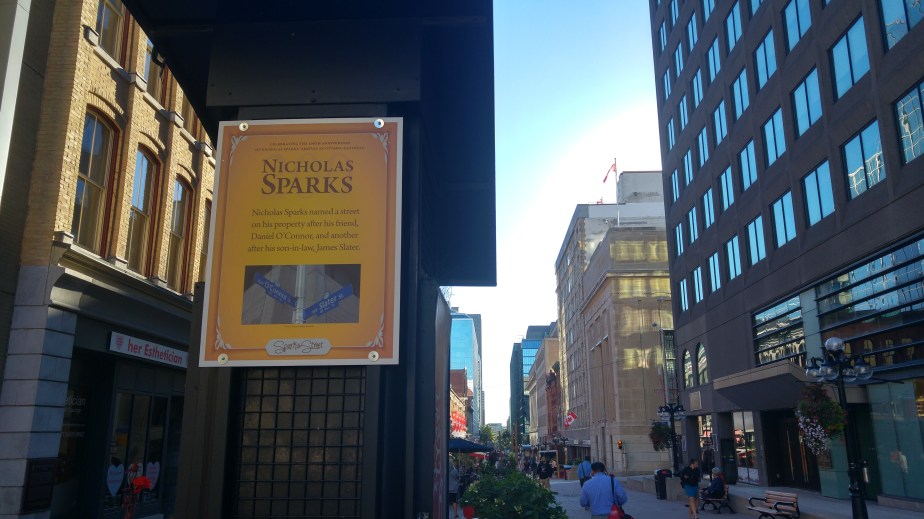

Over the summer of 2016 I had the opportunity to work on Ottawa’s historic Sparks Street as a social media coordinator, among other things.

One of my first projects working for the Business Improvement Area was a 200th year anniversary of Nicholas Sparks’ settlement into Bytown, today known as the Ottawa-Gatineau region. Sparks’ descendants were planning a giant hurrah! to celebrate their ancestor’s good fortune and hard work in collaboration with the Bytown Museum. My job was to find some fun facts about Nicholas Sparks and Sparks Street for posters to be hung up up and down the pedestrian walkway. Little did I know, I was helping to create what Pierre Nora would consider lieux de memoire in downtown Ottawa!

I was surprised the endeavour was launched by the family. There was only room to print one sentence of general historical information on each poster (an embarrassing misfortune for this MA History candidate with an 120 page thesis looming in the future), so the historical value is in somewhat dissolved. Pedestrians won’t immediately know some of the darker elements that complete the 200-year-old picture, but they will feel a slight reminder that the land they are standing on, eating lunch on, shopping on, has a deep connection to the past.

There are more posters on Sparks than there are pictured here. Go for a stroll downtown for to read the rest!

Tension is the invisible but unmissable, enduring force propelling public history and its historiography. Between the state and private institutions with funding; the academics behind the walls of the ivory tower; and the families and individuals whom they are reputed to serve, Ashton notes that the field is fraught with debate. Fostered by modernity and a growing interest in memory in the nineteenth century, Meringolo writes the public historian’s is a profession born in national park preservation efforts, expanded in the 1980s and 90s with consultations with the public, and today democratized by collaboration. According to Dick, individual narratives and collective affect are fundamental to public history. Therefore, it is essential to bring existing but “othered” modes of thinking into the academic and professional fold. But the question remains: How? How can the gatekeepers of history open their doors and work with the public to tell the stories they want to hear without delegitimizing their academic integrity?

Photo by Elliot Brown, Villa Carlotta – Tremezzo – back to front “C”.