This post is adapted from my Master’s thesis, entitled “Negotiating Chineseness in Diaspora: Traditional Chinese Medicine and Memory in Hong Kong and the Greater Toronto Area, 1960-2018”. This post is Part One of a five-part series, where I use a blog format to present and elaborate themes less-explored in my M.A. in History thesis. Part One: Introduction

Migrant memories of traditional Chinese medicine

Imagine this. A small child with a head of thick, raven hair gets an annoying cough and a drippy nose. At five or six years old, they are a little over a metre in height—barely tall enough to see over an imposing object in the kitchen. If the child stands on the tips of their toes they might be able to make out the image of someone very dear to them labouring over an odorous pot of boiling herbs and water.

Only a few hours ago, they were in a similarly pungent space with jars packed full of dried herbs, fruits, seafood, insects and more. Imagine this small child was sat down in a chair, or if they are particularly small, in their dear someone’s lap, and made to face a doctor. The doctor took their pulse. The doctor looked at their tongue. Then, the doctor weighed out what looked like a cacophony of dried things and gave it to the child’s dear someone. They instruct the child to take it to return to harmony.

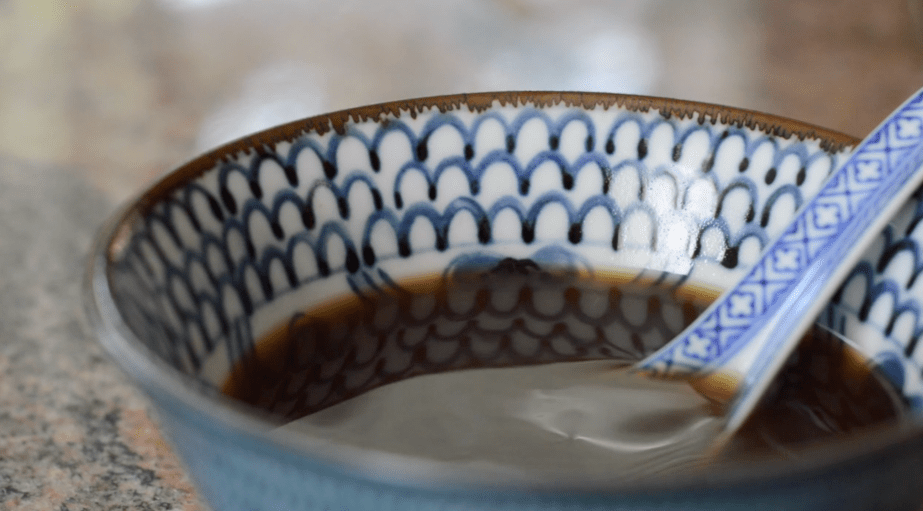

Now, imagine the kitchen again. The child’s dear someone pours the dark liquid into a bowl. The child takes a sip. It is bitter, but their dear someone might have placed some sweet, round, pinkish thin crisps on the table to eat with the bitter liquid. Haw Flakes 山楂餅 (sahn jah bang). The child is told to drink it all, and so they do. Every participant in my study shared a version of this narrative about being a child and being sick.

It is a memory so ubiquitous, so obvious, as common as the common flu.

From fall 2016 to fall 2018, I studied the construction of cultural identity through the microcosmic perspective of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) as culture for Chinese Canadians between two localities, Hong Kong and the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) for my Master’s research. I was interested in subjective questions of culture and identity. The main questions guiding my research were: what role(s) does traditional Chinese medicine play in cultural identity formation in trans-Pacific Chinese communities in Hong Kong and Toronto? How is the notion of Chineseness perceived, experienced, negotiated, and narrated by TCM practitioners and users? How do their perceptions, experiences, negotiations and narrations of TCM relate to family, caregiving, and community? I conducted 11 in-depth, face-to-face, oral history interviews conducted in Hong Kong and the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), 8 of which I analyzed in my actual thesis. I argue that Chineseness is found in the liminal spaces of their narrative identifications of self, their performances and transmission of knowledge in family, and their negotiation of Otherness in the TCM community in the GTA.

Traditional Chinese medicine is a liminal space where Chinese diasporic communities practice and express hybrid narrative cultural identities. The history of TCM is religious, socioeconomic, political, and deeply personal. TCM is an ancient form of healing built on a foundation of over thousands of years of practice. Sources range in the age of TCM knowledge and practice — it is likely 2,500 years old, but some say it could be 4,500 years old. It is comprised of herbal medicine, acupuncture, massage, cupping, moxibustion, exercise (eg. tai chi), and dietary therapy. At its most fundamental, the concept of TCM aims to balance two opposing principles in nature—feminine and negative 陰 (yin) and masculine and positive 陽 (yang)—to maintain the flow of vital life energy or 氣 (qi). TCM is not a monolithic canon of medicine as much as it is a “multi-sited, multidirectional, and sociohistorically contingent” set of practices and processes.

TCM is a system of knowledge of healing “made through—rather than prior to—various translocal encounters and from discrepant locations” (Zhan, 2009).

TCM arrived first in Canada with the immigration of Chinese workers in the mid-nineteenth century. In The Concubines Children, Denise Chong’s award-winning memoir about her grandmother May-ying’s struggle as an early immigrant in a Vancouver Chinatown, TCM was a consistent thread of daily life: “A line of pickle jars was her medicine cabinet […] For everyday use, to promote circulation, energy and vitality, were […] yuk choy, dong guai, ginseng and various grasses and tree barks” (Chong, 1996). In 1921, of the thirteen families among 2,035 documented Chinese in Toronto, three were herbalists (Chan, 2011). These early Chinese immigrants brought TCM with them in their suitcases, minds, and bodies in the form of texts, dried goods, seeds and more importantly—their rituals, practices, and memories. In Canada, herbal medicine and acupuncture are the most commonly practiced components of TCM.

Today, TCM is no longer restricted to immigrants and a few rare believers—70% of the Canadian population has tried TCM at least once. In the GTA, dozens of TCM colleges and clinics serve Chinese and non-Chinese populations. The usage of TCM is also modernizing; consumers take capsules, tablets, and tinctures in lieu of the traditional process of brewing and drinking herbal tea.

Throughout its history, TCM has been used across socioeconomic identifications and demarcations. The rural poor of 1960s Hong Kong practiced TCM in daily life as affordable and accessible healthcare. The educated and more prosperous Chinese immigrants in present day GTA practice TCM as a part of their culture as they can optimize their health with the combined usage of Western medicine. The participants in my study use TCM as ritual health care in daily life and as medicine to address acute illness. In the GTA, immigrants connect to Chineseness through daily life performances of TCM for self and for family.

The history of TCM in the GTA is intensely political. The evolution of TCM from those early ancient practices and texts has been affected by the geopolitical events in China in the early 20th century, from the conception of Chinese Western integrated medicine in the 1950s, to the abolition and persecution of TCM in the Cultural Revolution, to the modern system of combined traditional Chinese and Western medicine. It has been influenced by the politics surrounding the handover of Hong Kong in 1997, which would bring a ‘classic’ iteration of TCM to the GTA. It was influenced by Ontario regulation and the uneven negotiations of Chineseness within Chinese individuals and communities in the GTA. TCM has a translocal history influenced by capitalism, communism, movement and diaspora.

Traditional Chinese medicine is fiercely personal. It is a set of embodied practices rich with the subjective narratives of family and community, of personhood and identity.

TCM is embodied memory, affective practice, and transmitted knowledge—a basic part of Chinese diasporic life.

The heuristic examination of narratives of TCM practice in Chinese individuals in Hong Kong and the GTA opens a discursive space to explore diaspora, affect, and performance in their lived experiences. Hong Kong Chinese Canadian individuals living between Asia and Canada use their memories of TCM to perform, negotiate and transmit cultural capital. Chineseness is narrated in individuals, performed in familial roles, and negotiated in TCM communities.

People and practice are rooted in specific historical narratives influenced by real political, social, and economic events. They adapt as they traverse spatiotemporal routes. Both have the potential for healing and harm, flow multi-directionally, and are inscribed by generational memory. Like the Hong Kong Chinese diaspora in Toronto and Chinese Canadian diaspora in Hong Kong, traditional Chinese medicine also straddles constructed narratives of East and West. Placing these two elements—Chinese diaspora and traditional Chinese medicine—on either side of an imagined, conceptual mirror may coax out the interesting and meaningful differences and similarities in the myriad of reflections which comprise cultural identity.

This post is Part One of a five-part series, where I use a blog format to present and elaborate themes less-explored in my M.A. in History thesis.

References

Chan, Arlene. The Chinese in Toronto from 1878: From outside to inside the circle. Toronto, Dundurn: 2011.

Chong, Denise. The Concubine’s Children: Portrait of a Family Divided. New York: Penguin Books, 1996.

Zhan, Mei. Other-worldly: Making Chinese medicine through transnational frames. Durham, Duke University Press, 2009.